Meet The Maker: The inside story on how Guinness' surfer ad came to be

The Background

I’m blessed with having worked with some of the best people in the world, but I’m even more blessed to have been around when some of the most iconic, memorable and undoubtedly ground-breaking work has been created.

One of those moments in my life was when I worked at Abbott Mead Vickers. It was at a time when the creative department was packed with the kind of talent agencies can now only dream about.

Let’s start with the Guvnor David Abbott, then Richard Foster and John Horton, Tim Riley, Damon Collins and Mary Wear, Nick Worthington and John Gorse, Ron Brown, Peter Souter and Paul Brazier, Jeremy Carr, Dave Hieatt, Steve Hudson and Victoria Fallon, Malcolm Duffy and Paul Briginshaw… the list goes on and on.

There were over 100 yellow D&AD pencils on the shelves in that office and everyone had a good few under their belts.

One particular team, who I sat two offices away from, were a couple of guys called Tom Carty and Walter Campbell. They’d already become a couple of superstars and bagged nearly a dozen yellow pencils and a rare-as-hens’-teeth black ones for Dunlop ‘Tested for the Unexpected’ and a few Volvo films, ‘Twister’ being the most famous.

But the best was yet to come.

The Big Idea

AMV was put on the Guinness pitch list and Tom and Walt threw their hats in the ring to work on it. Well, why wouldn’t they? The two of them are Irish.

Back then Guinness was seen as an old man’s drink as if the elderly had nothing better to do with their time than wait for the three-parts pour.

‘We need this to be treated as if we are advertising lager’ were the client’s words. ‘We want to capture youth! Under no circumstances talk about the time it takes to pour a pint’.

Well good things come to those who stick by their guns… and the classic line ‘Good things come to those who wait’ was born.

As Walter states ‘the expectation of the Guinness during the pour was core to the Guinness experience. As many of my friends were Guinness drinkers, I’d seen how deeply they would engage looking at the pint being poured. I’d see how their imagination was firing at the thought of it’.

One image Walter found over that weekend was a beautiful, but very simple, shot of a Hawaiian surfer looking out to sea with his board across his knees.

That surfer had that same look in his eye, a sort of longing and satisfaction combined and that started the creative cogs whirring.

What They Did

It was to be the second film to be made for Guinness and it came pretty quickly after ‘Swim Black’ which, by the way, stated it takes 119.5 seconds to pour the perfect pint (so much for not mentioning time).

I remember Tom and Walt talking to me about a bloke who waits for a wave and then rides the wave, gets back to the beach, has a pint of the black stuff to celebrate as a white horse runs out of the surf in the background.

I was like ‘What? Is that it?’ I should have known better.

The next day I saw Walter wandering through the creative department with Walter Crane’s 1893 painting called ‘Neptune’s Horses’ under his arm and I knew then that something very interesting and magical was about to happen.

Saying that though, during the creative progress, Walt made a trip down to Cornwall to see what surfing was all about and have a chat with a few people and he and Tom toyed with the waves being made up of a pod of whales, as this is something they do and it’s called Wave Washing.

Thankfully they stuck with Mr Crane’s vision.

So they set about writing the premise. The agency and the client, Andy Fennell loved it and then they got Jonathan Glazer on board and started the production process.

Fast forward to being in a helicopter and landing on a very religious beach in Hawaii, where upon landing you had to say a prayer.

They also had to find the main man. No one wanted a polished actor or a model.

Glazer explains that they didn’t want the perfect face, but instead ‘Someone who looked like they would genuinely wait for this extraordinary wave and only they would know when it was going to come’.

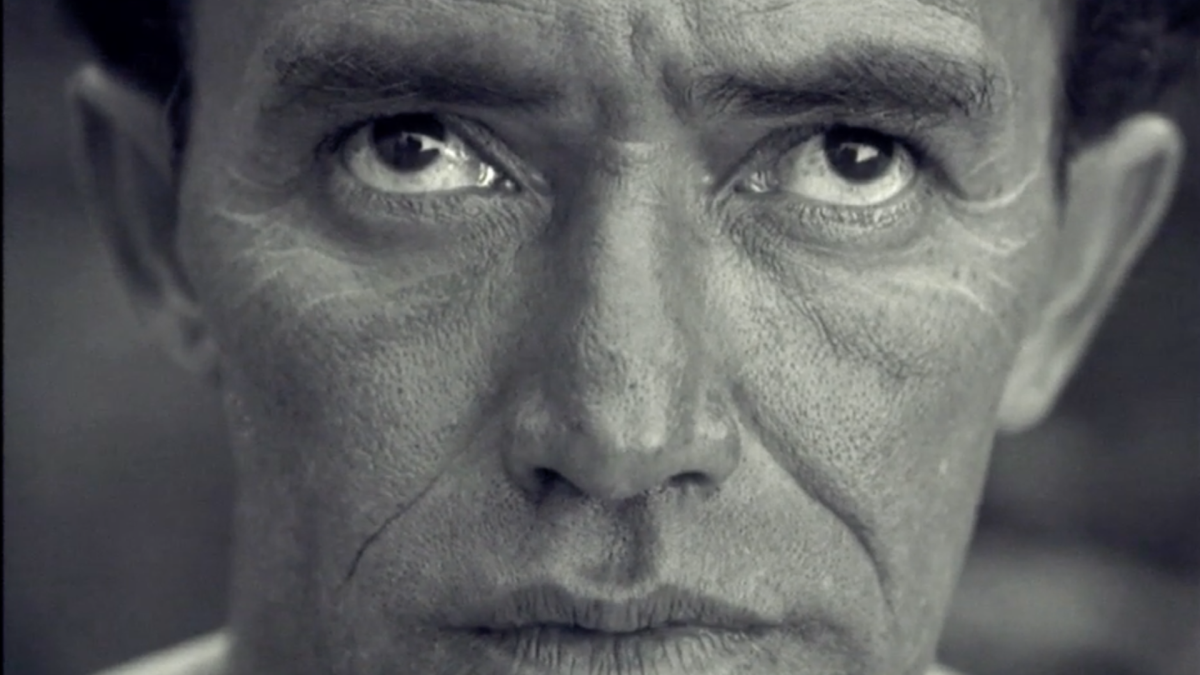

So trawling around the island they found ‘their star’ fast asleep under a palm tree. He also happened to have eyes which seemed to be pointing in different directions.

He was a local who, benefiting from hindsight, was probably more talented surfing the local talent than he was hitching an aquatic tube ride.

So he and three other more accomplished local surfers were jet skied out into the ocean where waves the size of a block of flats travelling towards you at 60mph form.

It was the equivalent of a Sunday league footballer hanging around the box in the Championship League ready to dazzle everyone with his skills.

The eight days of filming were to prove dangerous, ‘like filming an avalanche’ recalls Glazer. He gave the instructions to the ‘actors’ from a speedboat. The cameraman was hanging precariously off the end of the boat, trying to get those amazing shots. Sometimes all the crew were washed off the craft and had to wait several minutes before getting picked up from the surge.

The main surfer himself was far from an expert, and Glazer admits that he looked terrified by the ordeal. This, however, showed through in the final production and gave credence to the storyline, making his victory feel all the greater.

The sense of achievement becomes something quite tangible when the final shot of our Polynesian hero, who really has just completed the greatest and most terrifying surf of his life, concentrates on his eyes, like the steed’s wild eyes.

Then, back home in Soho along came the next challenge, adding the horses.

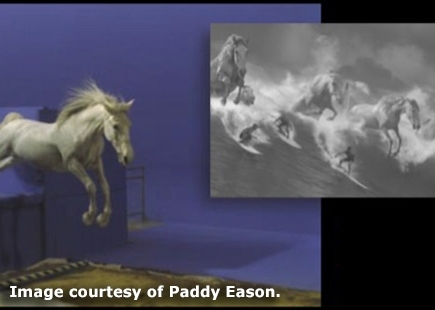

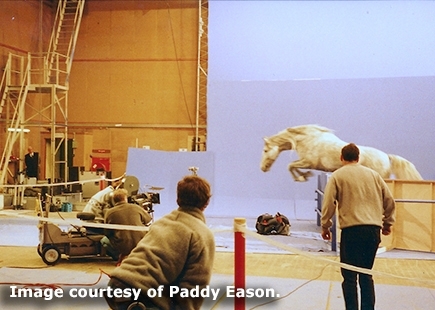

Glazer used Lipizzaner horses and had them painted with muscle tone so that the muscle definition would show up on film. He needed to make sure that the shots would match up and this led to three days of repeated shooting of the horses jumping over fences, a task even more difficult than filming the surfers.

I remember bumping into Jonathan at AMV. He was looking slightly ashen faced and biting his nails. I asked him ‘how’s it all going?’

We’d worked with each other previously on the Nike ‘Parklife’ commercial and I’d never seen him look so nervous.

‘I’m having problems with the horses’ he said. ‘I can’t get them to work. Maybe it works without them’.

‘Don’t be daft you need them. They are instrumental. They are the magic’ I replied. ‘You and the lads will make it work’.

Paddy Eason, a VFX designer and supervisor at The Computer Film Company recalls “It was a tough project. I remember very clearly that Jonathan Glazer was in the corner of one of the suites at CFC, with his head in his hands saying, ‘It’s all fucking shit.’ I’ll never forget. We did sometimes have dark moments where we didn’t think it could be done.”

Well thankfully a whole bunch of ultra talented, dedicated people who shared the vision of Tom, Walt and Jonathan made it happen.

Lastly, along came the icing on the cake.

Originally contemplating a Velvet Underground/Pink Floyd track, along with 50 others, Walter wanted a track that sounded like the blood pounding inside the surfer’s head when he surfs. Something that sounded dangerous.

They found a track created by British band Leftfield which felt just right.

Tom Carty knew a member of the band so they had a bit of an in. After a few tweaks and twiddles it was perfect.

This eventually formed the basis of a track called "Phat Planet" which appears on their 1999 album Rhythm and Stealth.

A drinking partner of Glazer’s called Louis Mellis, who was writing Gangster No1 at the time, (Jonathan was considering directing the film) had a 40-Malboro-a-day voice and he was asked if he’d mind reading the narration.

Dripping with meaning and reference to waiting for something momentous, a great moment, the fulfilment of a dream, whilst the thumping track completed the picture.

It was the last bit of the jigsaw, and I’d been there to see it completed.

The Review

Those 60 seconds were some of the most encapsulating and enthralling ever produced.

It wasn’t pure jingoism, sensationalist or tentatively cool, here today and gone tomorrow.

Instead it was crafted, thought-out and hypnotically captivating.

As well as getting just about every award going, it went on to win two British D&AD Gold awards, the only double Gold for 40 years.

I feel blessed.

If you enjoyed this article, you can subscribe for free to our weekly email alert and receive a regular curation of the best creative campaigns by creatives themselves.

Published on: